Read how Sydney Rainwater and Navya Shukla reported this piece, High need, low accessibility: Oglethorpe County residents face barriers to mental health care, even as teens and schools are willing to have the conversation for The Oglethorpe Echo, which was written through our participation with The Carter Center’s Mental Health Parity Collaborative. The collaborative is a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity and newsrooms in select states across the country. Editors included Nora Fleming, The Carter Center’s newsroom collaborative manager, and UGA Professor Andy Johnston, editor in residence for The Oglethorpe Echo. The students also consulted during the reporting process with Sofi Gratas, a former Covering Poverty contributor who graduated from the UGA College of Journalism and Mass Communication and now participates in the collaborative covering rural health and health care for GPB (Georgia Public Broadcasting).

Their reporting process ran from October 2023 through January 2024, with February and March 2024 devoted to editing and gathering images. The story was published in The Oglethorpe Echo on March 21, 2024. That day, the paper received a letter to the editor saying, “I congratulate the Echo on featuring a story on the difficulties and necessity of mental health care which you featured on the first page of this issue. My late wife suffered from severe mental health issues in her later life and the burden of them on both her and her family was substantial.”

Going into this story, my writing partner, Sydney Rainwater, and I were aware of the statewide need for better mental health resources and what the role our story could play in highlighting this need in a smaller community like Oglethorpe County. However, the challenge lay in finding the voices that could do the story justice. With an issue as sensitive and personal as mental health, and with a large part of the issue being the lack of conversation surrounding it, it took time to find the information and the sources that would pull our story together.

What helped us the most was relying on the community we were trying to cover. Because Oglethorpe County is so tightly knit, each source we talked to pointed us in another direction, connected us with someone new, or told us something we were missing. Even though we ended up interviewing an immense number of sources, and many of them couldn’t make it into our final story, each conversation painted a clearer picture of the issue we were addressing and gave our story more direction.

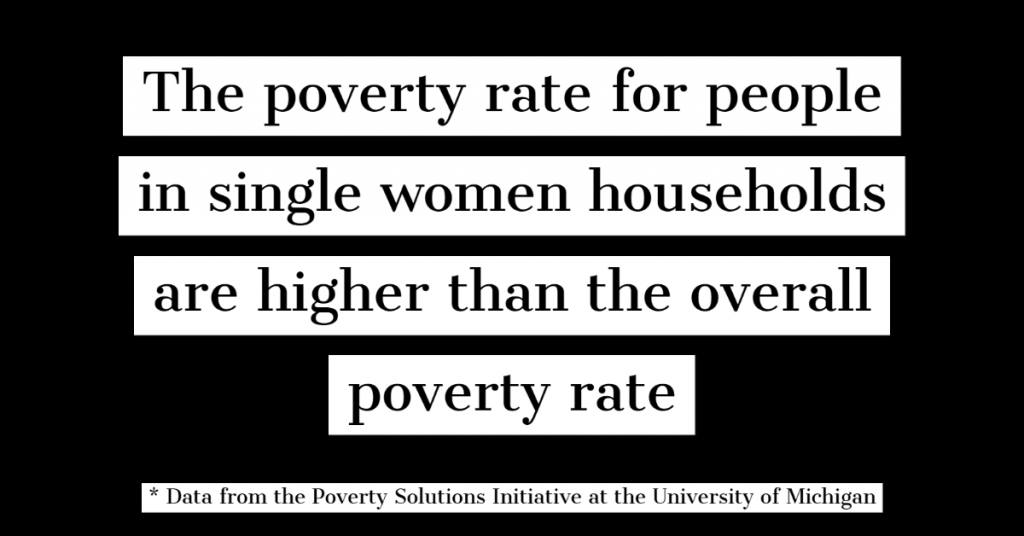

In-person interactions, such as when I visited Oglethorpe County Elementary School to take photos for the story, allowed me to see the work being done in the county and make a personal connection with the topic of mental health. Coming out of that classroom, where the students had spent the past hour exploring mental health strategies in such an open, welcoming environment, reassured me that the story we’d spent months of time and effort on mattered, and that it needed to be told.

The importance of relying on others for this story extended to my partner, Sydney, and our editors. Tackling such a complex topic, reaching out to as many people as we did and incorporating so many perspectives into our final product would not have been possible without the constant trust and teamwork between all of us throughout the semester. —Navya Shukla

My writing partner, Navya Shukla, and I started working on this piece almost as soon as we joined the Covering Poverty team last fall. From the start, we knew how impactful this story could be to the Oglethorpe County community and how important it would be to the larger mental health conversation. We each put forth our absolute best efforts because we believed in the story.

There were certainly challenges. Finding an informative yet positive perspective was a struggle at first. We interviewed countless sources, many of whom didn’t end up in the final product, because talking about mental health is still not easy. As time-consuming as it may have been, I found that the more in-person, casual conversations we had with sources and community members, the more secure I felt in the direction of the story.

Collaboration was the name of the game for this one. Our story would not be the same had we not leaned on each other for ideas, gathered advice from our editors and talked with as many sources as possible. —Sydney Rainwater