By Jacqueline GaNun

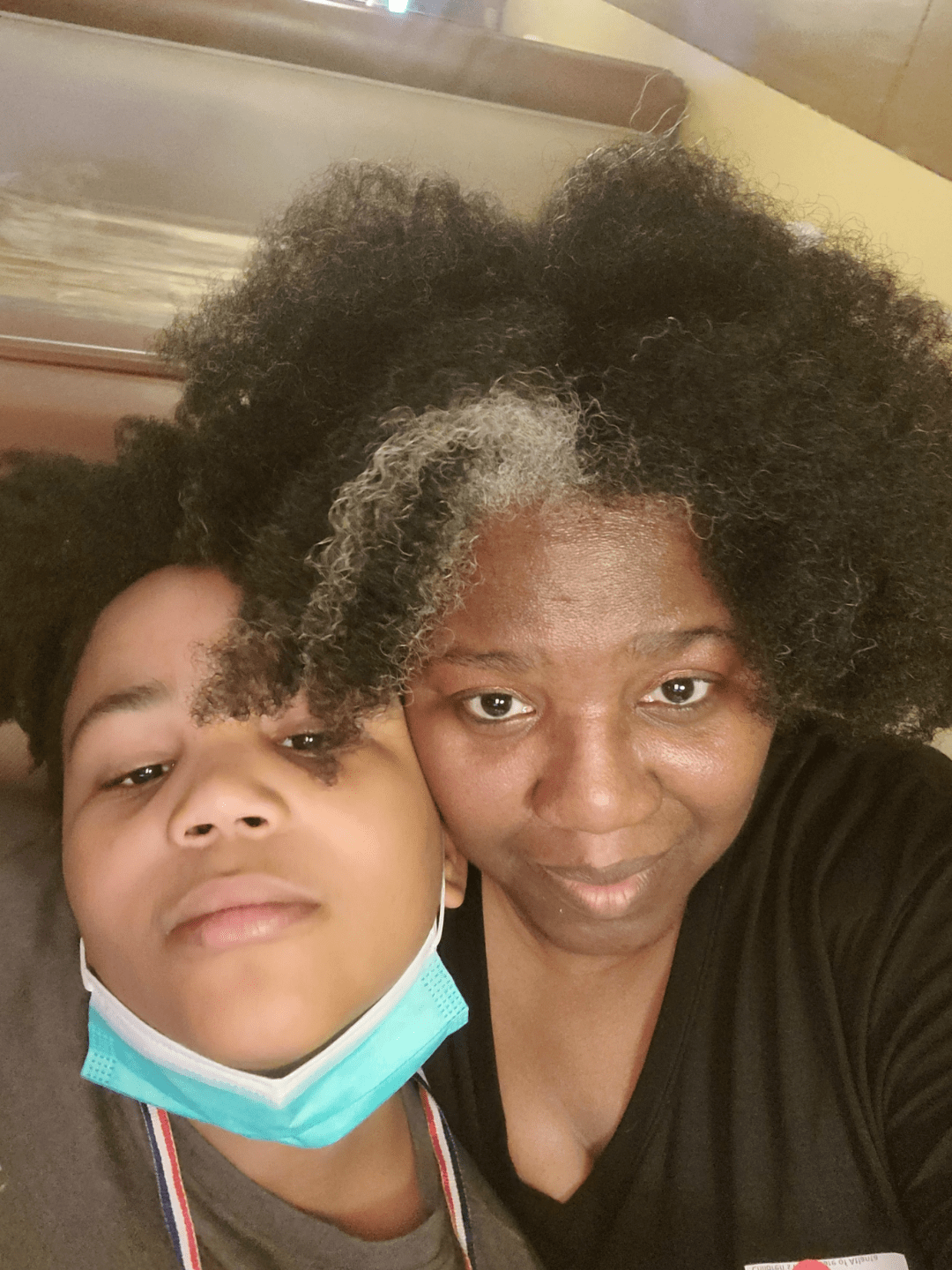

Kelli Lewis’ oldest son, Ahav, loves to design sneakers. He’s good at it, too. Lewis said she thinks his designs are “amazing,” and he could make it his career. But Ahav’s dreams have been stymied by what Lewis describes as inadequate care for his mental health conditions.

“I would love to say that one day he would have his own sneaker line and be sitting running his company,” Lewis said. “But I don’t know if he’s ever going to have the faculties to be able to do that.”

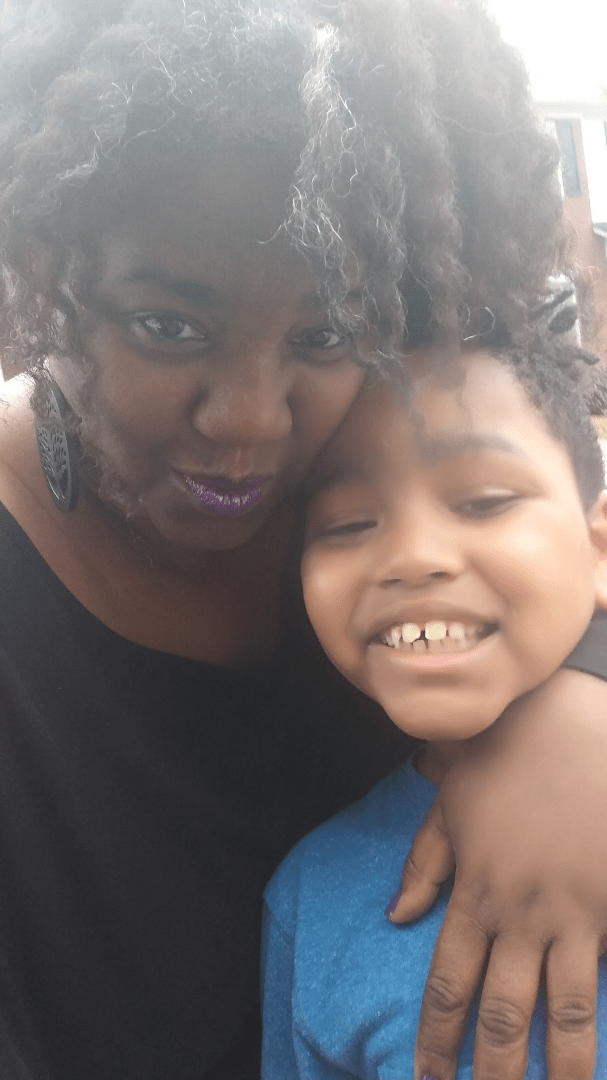

Ahav, who is 13, has been diagnosed with multiple severe mental illnesses. He hears voices and has trouble regulating his emotions and impulses, which sometimes affects his younger brother, Analiel, who is experiencing his own mental illnesses.

Lewis’ two sons are among the more than 14,000 children who have received care from Georgia’s mental health institutions, including in residential treatment centers and state psychiatric hospitals, according to federal data. Lewis said her sons have fallen through the cracks in a flawed system that needs fundamental change.

Gaps in Georgia’s care system

The root of Lewis’ struggles with the system is that the state does not have enough trained mental health providers, said Joe Sarra, an advocate at the Children’s Freedom Initiative. The state initiative created by the nonprofit Georgia Advocacy Office works to get children out of institutional settings into supportive communities.

Many of the flaws in Georgia’s care system stem from a lack of infrastructure when the state shut down many of its institutions around 2005, after which there weren’t enough community-based care services to route people to, Sarra said. Children ended up in psychiatric residential treatment facilities, “intermediate care facilities” and nursing homes. Of these three, the bulk of children are in residential facilities.

“The longer that kids are segregated away from their peers — their peers without disabilities — and they’re maintained in these congregate, segregated settings, they actually become more globally developmentally delayed,” Sarra said.

The number of children in residential facilities has increased over the years, Sarra said. He said it’s because the state doesn’t provide case management or inform parents of their rights. Foster parents also don’t receive adequate training or resources to foster children with disabilities, and they end up bouncing around between facilities and temporary homes, he added.

He and Lewis met a couple of years ago. At this point, Lewis said, they email just about every day.

“I knew that things weren’t being done correctly,” Lewis said. “I was just a mommy knowing, and Joe came with no, here’s the statute.”

Georgia’s mental health system, Lewis said, is not built to help her sons, who require more specialized and intensive care than other children. The programs of care, built around things like depression and anxiety, don’t work for what she describes as Ahav’s more intense conditions, including schizophrenia. Childhood schizophrenia is rare, affecting approximately 1 in 40,000 children. Yet pages of medical history and previous diagnoses don’t protect against medical professionals questioning Lewis’ son’s reality.

“Childhood psychosis has been happening for a long time,” Lewis said. “At what point are you all going to create a program, at least one in the state, for these kiddos?”

Ahav has been to every residential psychiatric facility in the state, moving in and out of treatment facilities for much of his life. Lewis said he’s fallen into a gap in the system — he doesn’t have a treating psychiatrist because they deem Ahav “too severe for outpatient.” Insurance requirements have also complicated his care and caused financial strain on Lewis’ family.

People with disabilities are more than twice as likely to live in poverty than people without disabilities, according to the National Council on Disability. Lewis, who lives in DeKalb County, is a single mother. She used to teach and perform as a singer, but had to quit her job to take care of her sons. Her music career is also on hold. She’s worked in the gig economy delivering groceries for Instacart and tries to work from home for a travel company, but she said it’s hard to schedule calls around caring full-time for Ahav and Analiel.

She and her family are on Supplemental Security Income Medicaid, a program that helps low-income people pay for medical care.

Lewis said sometimes Ahav knows he’s not ready to leave a treatment facility. The pair has sat in family sessions and he tells doctors if he does go home, he feels like he might hurt himself or his family.

“And he comes home the next day,” Lewis said. “Because insurance says he has to come home.”

Ahav gets discharged for whatever reason — because insurance won’t cover more nights in the hospital, or it won’t cover out-of-state treatment, or he didn’t experience a bad enough episode while in treatment. He goes back home, and then eventually back into an institution. Sarra said the treatment facilities that don’t work with families to provide care after discharging patients contribute to the “cycle of crises” that Ahav and others experience.

“I know special needs families from every demographic, and I don’t care how much money they started off this journey with, it doesn’t matter. It guts you,” Lewis said.

‘How do you get help like that?’

Children’s Freedom Initiative has helped families access more community-based care since its founding in 2005, Sarra said. But there remain kids like Ahav, who still hasn’t been able to get adequate care.

“The state should be recruiting providers who are trained and open to serving kids to have high-level behavioral needs,” Sarra said.

Lewis said she worries even more for her sons’ futures. As they get older, it’s becoming even harder to protect them. She is concerned about Ahav being with roommates who have sexual aggression issues.

She also said she fears encounters with the police. As Ahav grows out of childhood, in a criminal justice system that discriminates against Black people, especially those with mental illnesses, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, he is more likely than a white teenager to be sentenced to jail and less likely to receive care once he’s there.

“One of Ahav’s therapists told him, you know, dude, one day you’re gonna attack the wrong person. They’re gonna press charges. You’re gonna end up in juvie, not the hospital,” Lewis said.

In order for her boys to receive the care they need, Lewis and advocates like Sarra said there needs to be a shift in the way funding is allocated and how people view mental health. She said initiatives like the state New Options Waiver and Comprehensive Supports Waiver Programs — which provide home- and community-based services for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities — would be good resources, but there’s not enough funding. More than 7,000 people are on the waitlist for the waivers, according to state data. They are provided through the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

While Sarra said funding for the waivers should be expanded, it’s crucial for the state to train more providers, which he said is the cause of the problem.

“You have an institutional setting that is sending a child home with no services in place,” Sarra said. “If the parent brings the child home and has another behavioral crisis, the cycle begins again.”

Lewis envisions communities where kids and adults with disabilities can live on their own with support when they need it. Until the system shifts from a punitive to a more human-centered approach, Lewis said, kids like Ahav and Analiel will continue to fall through the cracks.

“How do you get help like that, when you’re being treated like you’re an offender, when you’re really just sick?” Lewis said.

Jacqueline GaNun is a fourth-year journalism major at the University of Georgia.

Note: This story serves as an exemplar piece and was published with grant funding from the UGA Institute on Human Development and Disability. Read here how GaNun reported the story.