Local, regional and national reporters have had to adapt their storytelling, sourcing and safety because of the worldwide effects of COVID-19.

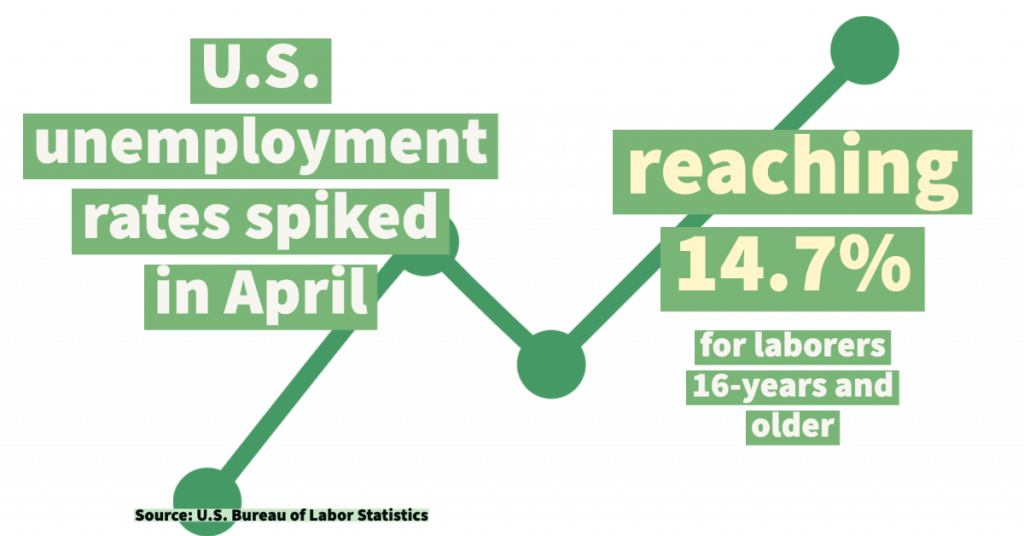

Notably, the economic effects of the pandemic since it reached the U.S. in early 2020 have resulted in massive layoffs across newsrooms. In April 2020, The New York Times reported an estimated 36,000 employees of news media companies had been laid off, furloughed or received pay cuts, including major corporations such as Gannett, Slate and Tribune Publishing. Poynter has also tracked layoffs, print suspensions, pay cuts and closures since April among small and medium newsrooms across the country.

As a result, many newsrooms have transitioned to digital formats and local reporters — including student-led newsrooms — have taken the lead in COVID-19 reporting for their communities. The spectrum of storytelling has expanded in tandem with major realizations about economic inequality and social disparities in the United States.

Vianna Davila, reporter with the ProPublica-Texas Tribune Investigative Initiative, authored a guide for reporters on covering homelessness specifically during the pandemic. Davila works within a poverty and homelessness beat. She encourages journalists to ask questions about outreach, Homeless Point in Time (PIT) counts and housing efforts, for example, in their own communities and learn relevant terms. Davila also makes a note about visibility.

“COVID-19 may result in homeless people becoming more visible,” Davila wrote in the presentation, posted by the National Press Foundation. “It doesn’t mean there’s a sudden increase in homelessness in a community … but, be mindful, that this situation could eventually result in more people being homeless.”

The “Broke in Philly” collaborative reporting project is an example of a regional approach to information gathering. Emphasizing reporting about poverty and economic mobility in Philadelphia, 19 news organizations are part of this collaborative where reporting is collectively presented on the “Broke in Philly” webpage.

Topics range from health and finance to housing and education, and there are bilingual media outlets involved. The reporting produced within this project has been important in starting conversations about the intersections of COVID-19 with food insecurity, environmental vulnerability and access to health care among Philadelphia’s at-risk communities.

Efforts like this show how journalists have adapted to covering poverty during a pandemic. The Pulitzer Center held a discussion on “Reporting on Disparities Across Vulnerable Communities During COVID-19” with three Pulitzer grantees who produced stories from within this focus point. They all had something to say about how safety concerns changed their approach to the reporting process, and how their approaches had to change as circumstances evolved.

Claire Napier Galoforo discussed her story for the Associated Press on the rural town of Dawson, Georgia, where she focussed on the impact of COVID-19 on a predominantly impoverished, Black community without affordable and accessible health care.

“It is a very careful calculation of risk and work. What value can we get in the field that we could not get over the phone?” Galoforo said during a Q&A segment. “Of course our worst fear is to go into a marginalized community and make things worse … I think that it’s something that we as an industry are going to be facing for a really long time as this virus continues to spread and continues to surge.”

Read Galoforo’s story here.

Reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Aisha Sultan, discussed her story on a single-mother in St. Louis, who in addition to experiencing poverty during the pandemic, had to home-school her kids in a dangerous neighborhood. She argued that the ability to connect virtually with people rather than relying on sporadic visits was helpful in her storytelling process.

“As a reporter, you need to be able to see certain things. I’ve asked Tyra to take me on a tour of the house on FaceTime,” Sultan said during a Q&A segment. “What ends up developing is a relationship that feels more intimate than me just showing up and then going away and then showing back up.”

Read Sultan’s story here.

Both reporters had to problem-solve and calculate risks when it came to reporting on these complex stories. This isn’t a new phenomena, but it’s especially relevant when stories depend on in-depth reporting and developing relationships with sources who might not have access to life-saving resources. When it comes to working with people experiencing homelessness or poverty, reporters have had to grapple with all of this.

A reporter in Jackson, Mississippi, Anna Wolfe, won a National Press Foundation award for her story and photo essay “Are the kids alright?” emphasizing the experiences of families and children adapting to an upended public education system. In a city with a 27% poverty rate — according to the U.S. Census Bureau — and where Wolfe reports four in 10 children live in poverty, Wolfe’s story analyzes how the pandemic exacerbated an already dire problem.

Read Wolfe’s story here.

Wolfe was one of the first reporters to receive the NPF’s new Poverty and Inequality award for reporting on children in poverty in the U.S. But where Wolfe’s story focussed on inequality, it also presented solutions being led by people in the Jackson, Mississippi, community.

As important as reporting on empirical data has been to the public’s understanding of how this pandemic affects people living in poverty — daily case numbers and tracking federal funding comes to mind — this shift toward solutions journalism in many newsrooms has been just as essential in order to show community responses in a larger context.

The Solutions Journalism Network is a nonprofit organization that emphasizes resources to help reporters cover stories from a solutions journalism perspective. Through the solutions journalism “Story Tracker,” reporting can be narrowed down by issue areas, location of response and media type, among others.

COVID-19 reporting has its own place on this website, highlighting stories about a “Racial Equity Rapid Response Team” in Chicago and food banks in Minnesota that switched to a delivery model to address food insecurity in rural and suburban communities. In an article published by the International Center for Journalists in discussion with Linda Shaw, editorial director at the SJN, this kind of “evidence-based reporting” on responses to local and regional problems is suggested as “essential” for communities to learn from one another.

Sofia Gratas graduated in fall 2020 with a journalism degree from the University of Georgia.